No Loose Threads In Banaras

One of the most exquisite fabrics in India, Banarasi textiles are known for their fine lustrous silk, silver and gold zari work in meticulous hand weaving and opulent embroidery. Adorned with a compact weave, metallic visuals, jaal and meenākāri work, Banarasi textiles carry within them the intertwined legacy of inherited memories, dying traditions and evolving identities that are multi-hyphenated.

Once the patterns evoke the desired effect on the socio-cultural fabric of Banaras, they are enclosed between elaborate borders that contain this syncretic narrative of ‘divinity in multiplicity’ before reaching the final step- cutting off the loose threads!

.jpg)

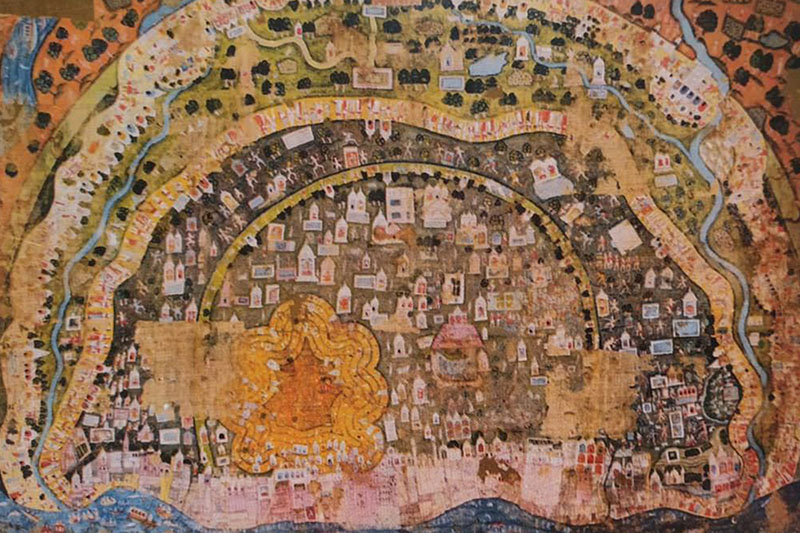

Reproduction of a ‘qanat’, Textiles from the City of Light

“Kāshyām mera naam mukti”— Death in Kāshī is Liberation! Cutting off the loose threads takes on a much greater symbolic significance in the sacred city of Banaras than in the rest of India. Diana L. Eck, in Banaras: City of Light, posits, “it is here that life is lived in the perpetual presence of death”. More than the coveted silks and brocades, enchanting Gangā ārtīs along the ghāts, temples, and artistic wealth, Banaras is known for its promise of moksha or mukti.

Tracing the threads of mysticism, integral to the city, it is fascinating to note that death which is enveloped in a shroud of terror and impurity elsewhere, in the City of Light, is holy. According to Hindu mythology, Yamrāj is the lord of death. After the judgement of one’s acts, he categorises them as good and evil to decide the fate of a person’s afterlife. In Banaras, however, Yama is not allowed within city limits, so dying in this sacred city means one can escape the cycle of life and death, heaven and hell.

Nestled on the banks of Gangā, Banaras is believed to offer another layer of protection from the relentless circle of birth, death and reincarnation. An often-quoted verse of the Mahābhārata claims, “If only the bone of a person should touch the water of the Ganges, that person shall dwell, honoured, in heaven.” In a spiritual pursuit to find meaning in death and seek salvation, people come from all over India to live in Banaras until they die, for dying a good death is as important as living a good life.

The City Plan of Varanasi, 18th century CE, National Museum, New Delhi

His death in Benares

Won’t save the assassin

From certain hell,

Any more than a dip

In the Ganges will send

Frogs – or you – to paradise.

My home, says Kabir,

Is where there’s no day, no night,

And no holy book in sight

To squat on our lives.

–Kabir, translation by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

These lines from Kabir’s poem ‘His Death in Benaras’ reflect the pluralist heritage of the holy city of Banaras. Eck notes, in the medieval past and in contemporary times, many poets with diverse views on religiosity have been attracted to the composite culture of Banaras.

Saint Kabir with Saint Ravidas, c. 1625 CE, National Museum Collection

In the city “older than history, older than tradition, older even than legends'', the weaving tradition is deeply embedded in its cultural conscience. While kaseyyaka, the silk of Banaras, is mentioned in Pāli literature as being worth a hundred pieces of silver, it has been speculated by art historians that the varied patterns displayed in the Ajanta murals of the Gupta period represent brocade specimens by tracing their resemblance with the early motifs. As a pre-eminent centre for Hindu rituals of rites of passage, Banaras has contributed to the circulation of ideas, oral traditions and brocades across various cultures.

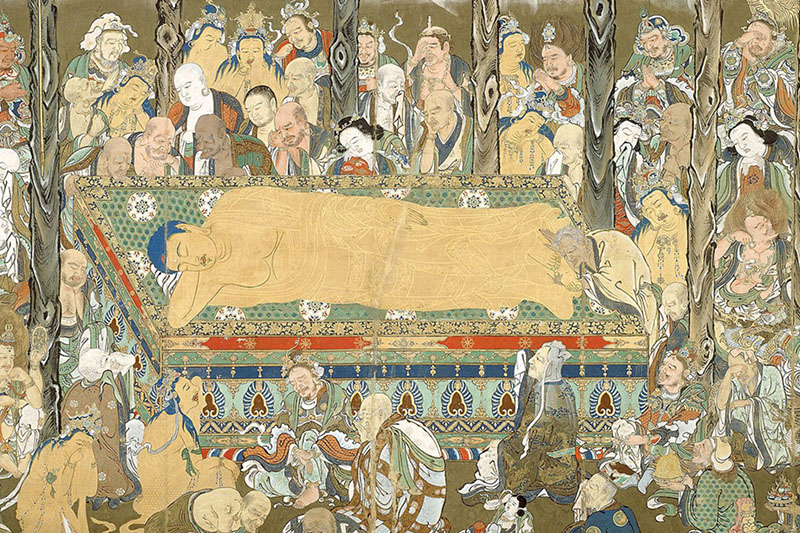

As per the legends, when Buddha attained Mahāparinirvāna, meaning “great, complete nirvāna”, his mortal remains were wrapped in a Banarasi fabric radiating with rays of yellow, red and blue colours. Another interesting example would be the early 17th-century Mughal painting, “Jahangir Holding a Portrait of Akbar”, which shows Jahangir magnificently dressed in intricate golden brocade and fine jewels, holding the portrait of Akbar, bathed in a divine transcendental light, in his plain white garments. Art historians have interpreted this contrast in clothing and their demeanour as rather ironic. As Kavita Singh argues, it almost seems that the deceased monarch seems more ‘real’ than the king who is alive!

The Death of the Buddha (Parinirvāna), c. 1921, Art Institute of Chicago

Chalti chakki dekh kar, diya Kabira roye

Dui paatan ke beech mein, sabit bacha na koye

(Seeing the grinding stone turning, turning, Kabir began to weep

Between the two stones, not a single grain is saved!)

The verse is often accompanied by a vivid folk-art depiction of a woman turning the simple domestic grinding stone, throwing not grains but people into the mill, where they are sure to be crushed between the two stones. Death is as common, as certain, as the grinding of wheat once it is thrown into the mill.

Banaras holds multitudes- of beliefs, stories and realities- weaved into a timeless tapestry that ties together all the loose ends just to unravel it all over again. Relish the undying charm of the city through its ghāts, lyrical heritage, textiles and mysticism through the philosophy and poetry of Kabir at the sixth edition of the Mahindra Kabira Festival, scheduled to take place from November 18-20, 2022. Join us to experience the intangible “oneness amongst diversity” through the unparalleled power of music, literature and the arts.

Mahindra Kabira Festival

Diksha Bisla

Write your comment here